When a criminal defendant goes on trial for their alleged crimes, there are two options available to arrive at a verdict of guilt or innocence. The first option, which most of us are familiar with, is a jury trial. Twelve jurors, along with a number of alternates, hears the testimony and examines the evidence presented. They are instructed by the judge as to what the law is, and then they begin their deliberations.

All, or nothing at all

In order for a jury to reach its verdict, their vote must be unanimous, either for guilt or innocence. It makes no difference whether a deadlocked jury is split evenly down the middle, or 11-1 in favor of conviction or acquittal. Unless all twelve jurors can agree on a verdict, the judge will declare a mistrial. While the efforts of jurors, attorneys, court reporters, and judges may seem to be wasted when a mistrial occurs, the constitutional rights of a criminal defendant are preserved. As none of us would willingly give up our own rights as Americans, neither should criminal defendants be expected to forfeit theirs.

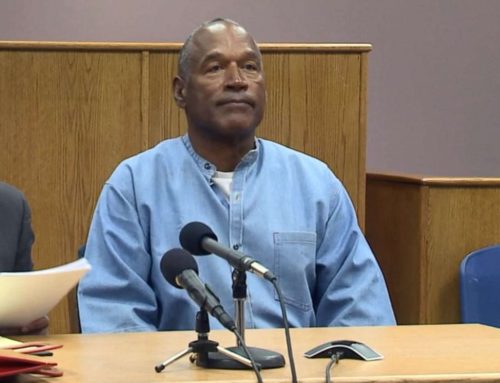

A recent criminal defendant, who had previously stood trial on several occasions for the disappearance and presumed murder of his wife, elected to take the other available route and request a bench trial. This decision is a risky one, because the concept of “judge, jury, and executioner” relies on a separation between the three roles. By allowing the judge to act as the jury in deciding the guilt or innocence of a defendant, there is no room for error on the part of the defense. The judge literally holds the life of the defendant in his or her hands in such a situation.

When judge and jury are one

Perhaps it was the prospect of yet another mistrial that convinced the defense to take a different approach with the fourth trial. The judge could either find for or against the defendant, but at least there would be no need for additional trials, one way or the the other. The third time was not the proverbial charm in this matter, but a jury trial virtually guaranteed some finality from the fourth trial, at least.

At trial, the judge asked witnesses to clarify their statements, and assessed the weight of evidence against the defendant in the same manner as a jury would. The judge also allowed a third-party defense to be presented, theorizing that others had committed the crime, instead of the defendant.

A verdict, at last

The trial judge did not need to instruct the jury as to what the relevant parts of the law were. The judge’s understanding of the law, and the decisions he made about the evidence presented at trial, were enough to arrive at a verdict of not guilty. With the opportunity for another deadlocked jury removed, the judge–as a jury of one–ending the possibility of further legal jeopardy for events from over a decade ago.

While the United States constitution provides protection against double jeopardy, this does not mean that multiple trials cannot occur. Have a criminal charge in New York? Let the AX criminal team offer you a free case consultation anytime; (518) 675-3094.

DISCLAIMER: The exclusive purpose of this article is educational and it is not intended as either legal advice or a general solution to any specific legal problem. Corporate offices for Nave Law Firm are located at 432 N. Franklin Street, Suite 80, Syracuse, NY 13204; Telephone No.: 1-866-792-7800. Prior results do not guarantee a similar outcome. Attorney Advertising.